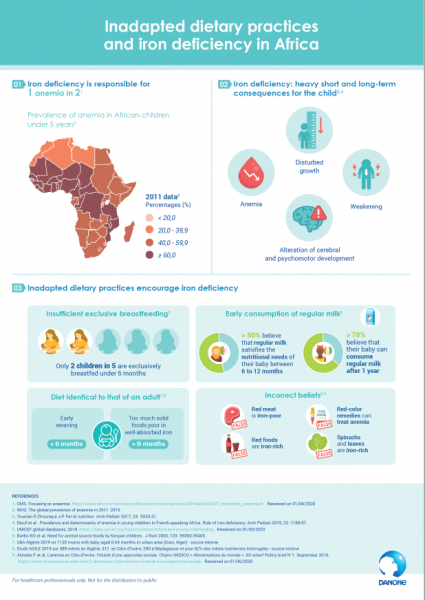

Iron deficiency is responsible for one in two anaemias1. In Africa, this is mainly caused by a lack of iron intake linked to malnutrition or certain inadequate food practices, in children already hard hit by infections and parasitic diseases2-5.

INSUFFICIENT EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING and early consumption of REGULAR milk

First of all, exclusive breastfeeding may be insufficient. Indeed, only 2 out of 5 children benefit from it up to 6 months6. In many cases, adapted milks are replaced too early by regular cow’s milk, containing low absorbable iron, which does not meet the child’s needs7,8. For example, more than 50% of Algerian mothers believe that regular milk meets their baby’s nutritional needs between 6 and 12 months, and more than 70% of Ivorian mothers believe that their baby can consume regular milk after 1 year old7.

A diet identical to that of AN adult

From the age of 6 months, the use of a well-absorbed iron-rich supplementary diet is necessary to cover the child’s growing needs, in addition to breast milk or an infant formula for non-breastfed infants9. Unfortunately, this food diversification is sometimes achieved prematurely – between 4 and 6 months in 70% of cases in Algeria10 – and children move too quickly to a diet identical to that of an adult, low in well absorbed iron2.3,5. In fact, only 44% of children aged 6 to 24 months received iron-rich foods in the last 24 hours, according to a survey of 8 French-speaking African countries2.

MISTAKEN beliefs

The use of ineffective red-coloured traditional remedies to treat anemia or the adoption of incorrect beliefs can aggravate iron deficiency7,11. For example, in Ivory Coast, more than 80% of mothers think red meat is low in iron7. Similarly, there are other beliefs such as spinach leaves and infusions/decoctions of teak or anango leaves or red foods (bissap juice, beetroot, mix of coca cola® and tomato concentrate) that are rich in iron11.

Find the interview of Professor Nezha Mouane at the 11th edition of the African Meeting of Infant Nutrition (RANI) on the state of the art of iron deficiency in Africa:

Infography : Unadapted dietary practices and iron deficiency in Africa

References

- OMS. Focusing on anaemia. https ://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/WHOandUNICEF_statement_anaemia/fr Consulté le 06/01/20

- Diouf S et al. Prévalence et déterminants de l’anémie chez le jeune enfant en Afrique francophone – Implication de la carence en fer. Arch Ped 2015 ; 22: 1188-97.

- Mwangi MN et al. Iron for Africa – Report of an expert workshop. Nutrients 2017; 9, 576; doi:10.3390/nu9060576.

- WHO. https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/ida/fr/. Consulté le 18/09/19.

- Bwibo NO et al. Need for animal source foods by Kenyan children. J Nutr 2003; 133: 3936S-3940S.

- UNICEF global databases, 2018 https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child Consulté le 06/01/20

- AGILE study 2019 on 389 mothers in Algeria, 312 in Ivory Coast and 290 in Madagascar – Danone internal source.

- Tounian, P., and J-P. Chouraqui. “Fer et nutrition.” Archives de Pédiatrie 24.5 (2017): 5S23-5S31.

- Brannon PM et Taylor CL. Iron Supplementation during Pregnancy and Infancy: Uncertainties and Implications for Research and Policy. Nutrients 2017; 9: 1327; doi:10.3390/nu9121327.

- U&A Algérie 2019 on 1120 mums with baby aged 0-24 months in urban area (Oran, Alger) – source interne Danone.

- Akindes F et al. https://www.chaireunesco-adm.com/L-anemie-en-Cote-d-Ivoire-l-interet-d-une-approche-sociale. Consulté le 09/09/19.

BA20-464