Each year, approximately 15 million infants are born before 37 weeks of amenorrhea (WA), and this number is rising1. These premature infants face the risk of complications at birth as well as over the long-term, especially when born extremely premature and with a low birth weight. Meeting the challenges of prematurity requires that these infants be given specific care.

Globally, prematurity affects 1 in 10 children. This figure masks, however, substantial geographic disparities: while prematurity rates are estimated at around 5% in several Scandinavian countries, some African countries report rates of over 15%. Of the ten countries with the highest preterm birth rates, eight are in Africa (Malawi, Comoros, Congo, Zimbabwe, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Gabon and Mauritania). The preterm birth rates in these countries reach as high as 18.1%.2

HIGH MORTALITY

Although the neonatal mortality rate linked to prematurity is declining, it still accounted for nearly one million deaths per year in 2015. Premature birth is the leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age1.

Neonatal mortality depends both on gestational age at birth3 and, independently of this, the baby’s weight at birth4.

The major physiological landmarks

Prematurity is categorised under two principal dimensions:

| By gestational age: | By weight at birth: |

|---|---|

| o Extremely preterm: < 28 weeks of amenorrhea (WA) o Very preterm: 28 to 32 weeks WA o Moderate to late preterm: 32 to 37 weeks WA | o Extremely low birth weight: < 1 kg o Very low birth weight: < 1.5 kg o Low birth weight: < 2.5 kg |

“Even relatively late, prematurity should not be trivialised: the risks of motor disability or intellectual disability are 2 to 3 times higher in children born at 34-36 weeks than in children born at term.” Torchin et al, 20153

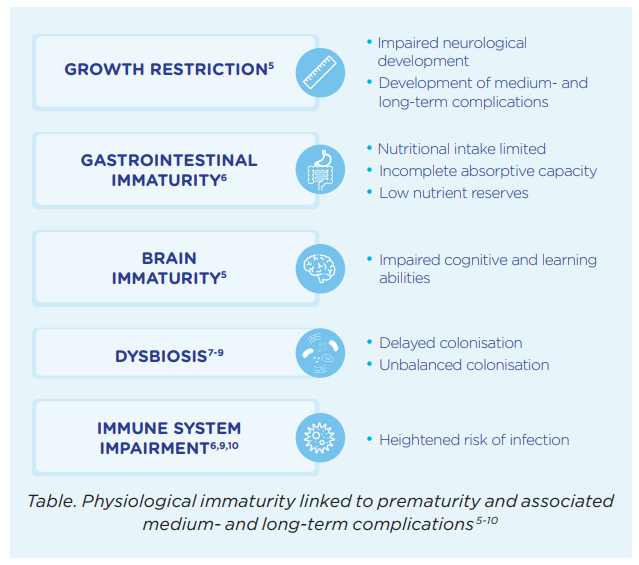

PHYSIOLOGICAL IMMATURITY AND COMPLICATIONS

Premature babies are born at a time when their growth rate is at its peak and when the in utero development of their digestive and immune systems, brain and lungs is still incomplete. Premature infants are therefore more likely to suffer from complications at birth (including the risk of death) and are, in the medium- and long-term (see box), at an increased risk of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases in adulthood.

NOURISH, OXYGENATE AND KEEP WARM

The primary challenge is nutrition. In addition to having an immature digestive system, before 34 weeks the sucking and swallowing reflexes have yet to be acquired. Food must therefore be administered gradually, first parenterally (intravenously) if necessary, then enterally (nasogastric tube) as soon as possible in order to optimize nutritional intake and finally orally. Meeting this challenge results in a substantially reduced risk of short- and long-term complications associated with physiological immaturity of premature babies.Two other challenges to the infant’s survival and future health must nevertheless be met too: oxygenating and warming. In most cases, very premature babies require respiratory assistance as well as support to ensure their thermoregulation.

WHY SPECIFIC NUTRITIONAL CARE?

Premature infants have greater nutritional needs than those born at term11. Moreover, meeting these needs requires that nutrition should be gradually modified according to the infant’s weight and stage of development.

Hence, in order to ensure that the most suitable nutritional solution possible is provided, ESPGHAN has set out guidelines11,12 which take into account the weight of the premature infant (<1,800g or > 1,800g), its stage of development and its access to breast milk.

Indeed, some premature babies weighing more than 1,800g or those ready to leave the maternity ward will be exhibiting a persistent delay in their growth. In order to make up for this delay and thereby prevent the development of metabolic diseases in adulthood a gradual adaptation of the diet is recommended.

“The major goal of enteral nutrient supply to these infants is to achieve growth similar to foetal growth coupled with satisfactory functional development.”11

References

- 2018. Preterm birth. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth Last consulted 1 Nov. 2021

- Blencowe H et al. 2012; 379 (9832):2162-72.

- Torchin H et al. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2015 ; 44(8) : 723-31.

- Cutland CL et al. 2017 Dec 4; 35(48 Pt A):6492-6500.

- Lapillonne A, Griffin IJ. J Pediatr. 2013 Mar;162(3 Suppl):S7-16..

- Neu J, Walker WA. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 20;364(3):255-64.

- Butel MJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007 May;44(5):577-82.

- Magne F et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005 Oct;41(4):386-92.

- Santos IS et alBMC pediatrics. BMC Pediatr. 2009 Nov 16;9:71.

- Natarajan G, Shankaran S. Am J Perinatol. 2016 Feb;33(3):305-17.

- Agostoni C et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Jan;50(1):85–91.

- Aggett PJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006 May;42(5):596-603.

BA21-680