Several maternal or environmental factors can promote the appearance of a dysbiosis such as taking antibiotics, but also the mode of delivery1-5. This gut microbiota’s imbalance can have a significant impact on infants’ short- and long-term health1,2.6,7.

CHARACTERISTICS AND CONSEQUENCES OF DYSBIOSIS

Dysbiosis is an unbalanced composition of the gut microbiota7.

There are three types of dysbiosis that are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. They’re reflected in7:

Early dysbiosis, occurring in the first months after birth, increases in the short term the risk of respiratory infections, other infections (cystitis, sepsis…) or even infant colic1,8. But an altered microbiota can also lead to long-term conditions such as increased risk of celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, obesity, atopy and asthma, or allergies and allergic rhinitis1,2,9,10.

WHY DOES C-SECTION INFLUENCE THE BALANCE OF THE INFANTS’ GUT MICROBIOTA?

C-section is an essential procedure for some deliveries and its recommended rate by WHO is 5-15% of births11. In some countries, this percentage is much higher, but overall, it tends to increase by about 4.4% per year12. In West and Central Africa, caesarean birth rates are low (4.1%), while they are higher in North Africa (29.6%)13.

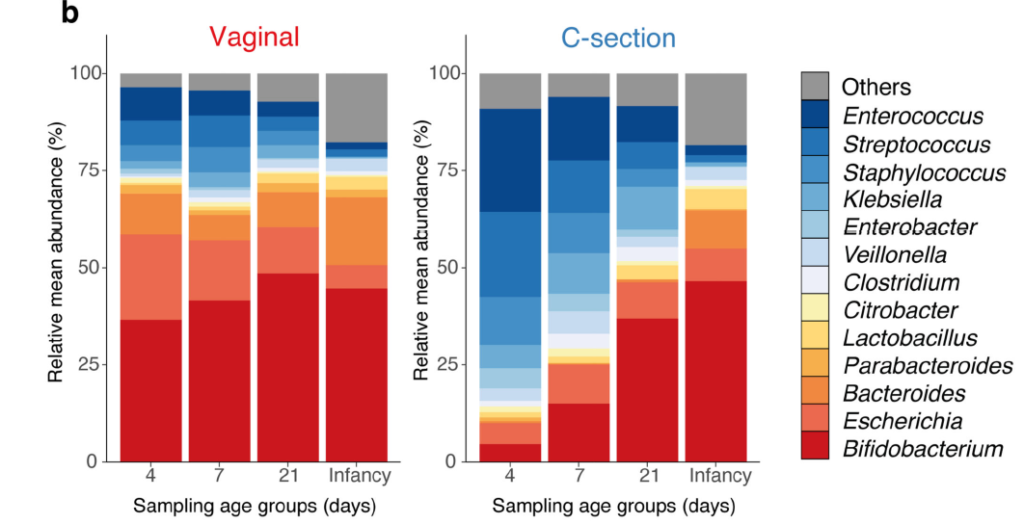

Infants born vaginally have a gut microbiota colonized by the mother’s fecal and vaginal bacteria, which are a majority of Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides. However, infants born by c-section do not benefit from them, because they are mostly exposed to bacteria from the hospital environment1,5,6. The composition of their gut microbiota is then dominated by the genus Clostridium (Clostridium difficile in particular) in the first three months1,14,16.

Adapted from Shao et al. (2019)16

REBALANCE THE INFANT’S GUT MICROBIOTA

Nutrition, including breastfeeding, plays an essential role in the rebalancing of the gut microbiota1,17. The beneficial bacteria and the prebiotic HMOs* present in breast milk work in synergy to restore the balance of the gut microbiota and support the baby’s immune system17. For non-breastfed infants, there are infant formulas that contain a combination of prebiotics scGOS/lcFOS** (9:1) and probiotics Bifidobacterium breve. This combination restores the microbial balance and promotes the development of a healthy immune system18,19.

To learn more about the effects of synbiotic-containing infant formulas on the gut microbiota of infants born by c-section, read the article on the clinical study of Chua et al. 2017.

References

*HMOs = Human Milk Oligosaccharides

**scGOS/lcFOS = short-chain galacto-oligosaccharides, long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides

- Munyaka, et al. “External influence of earlychildhood establishment of gutmicrobiota and subsequenthealth” Frontiers in pediatrics 2 (2014): 109.

- Tanaka et al., Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergology International. 66 (2017) 515-522

- Bischoff, Stephan C. “‘Gut health’: a new objective in medicine?” BMC medicine1 (2011): 24.

- https://www.inserm.fr/information-en-sante/dossiers-information/microbiote-intestinal-flore-intestinale 05/09/2019

- Penders, John, et al. “Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy.” Pediatrics2 (2006): 511-521

- Fujimura, Kei E., et al. “Role of the gut microbiota in defining human health.” Expert review of anti-infective therapy4 (2010): 435-454.

- Petersen, et al. “Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease.” Cellular microbiology7 (2014): 1024-1033

- De Weerth, Carolina, Susana Fuentes, and Willem M. de Vos. “Crying in infants: on the possible role of intestinal microbiota in the development of colic.” Gut Microbes5 (2013): 416-421

- Girbovan, Anamaria, et al. “Dysbiosis a risk factor for celiac disease.” Medical microbiology and immunology2 (2017): 83-91.

- Butel, M-J., A-J. Waligora-Dupriet, and S. Wydau-Dematteis. “The developing gut microbiota and its consequences for health.” Journal of developmental origins of health and disease 9.6 (2018): 590-597

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, «Déclaration de l’OMS sur les taux de césarienne », 2015 ; 8 ; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/161443/WHO_RHR_15.02_fre.pdf;jsessionid=8E57A0E97438BD9294176466A686FF88?sequence=1 [consulted October, 1st 2020]

- Harrison MS, Goldenberg RL. Cesarean section in sub-Saharan Africa. Matern Health Neonatal Perinatal. 2016;2:6

- Boerma T et al, Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean, Lancet 2018

- Rutayisire E, Huang K, Liu Y, Tao F. The mode of delivery affects the diversity and colonization pattern of the gut microbiota during the first year of infants’ life: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):86. Published 2016 Jul 30. doi:10.1186/s12876-016-0498-0

- Dominguez-Bello, Maria G., et al. “Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences26 (2010): 11971-11975.

- Shao, Yan et al. “Stunted microbiota and opportunisticpathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth.” Nature vol. 574,7776 (2019): 117-121.

- Scholtens, Petra AMJ, et al. “The early settlers: intestinal microbiology in early life.” Annual review of food science and technology 3 (2012): 425-447

- Chua M, et al. Effect of Synbiotic on the Gut Microbiota of Cesarean Delivered Infants: A Randomized, Double-blind, Multicenter Study JPGN, 2017;65:102–106.

- Wopereis H, et al. The first thousand days – intestinal microbiology of early life: establishing a symbiosis, Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 2014; 25;428-38.

BA20-765